Gay Men

Will Be Cruising

No Matter What:

Transgressive Queer Pleasure as World-Making Praxis

Gay men will be cruising no matter what, even during a global pandemic, when intimacy and social proximity are targeted as the main vectors of spread. Cruising—a practice consisting of gay men gathering in public spaces for anonymous sex—is transgressive in more than one way; it goes against the social, sexual ,and spatial norms constitutive of heteronormativity. It is a guilty pleasure that bears a transformative potential in this “guiltiness”. Drawing from José Esteban Muñoz’s notions of queer futurity, this paper suggests an understanding of cruising as a critical spatial practice that holds world-making capacities, creating “queer enclaves” within urbanity. The main method employed in this project is a combination of documentation (fieldwork) and representation (architectural drawings) taking the form of a critical inventory of cruising grounds around the province of Québec, Canada. The research-by-design project drifts between and across disciplines, affecting the same queer world-making potentialities found in cruising

Guilt and shame are two distinct emotions, even if they seem interchangeable at first sight. The “ideal son-in-law,” as it translates in English, is a French-Canadian saying used to point out a young man’s respectability. It is also a play on word as it refers, in the context of this article, to Joël Legendre name (literally Joël The-In-Law) and his former reputation.

Legendre was at the height of his career in 2015. The actor and director was everywhere to be seen in the small Québec’s show business industry, either as a successful radio host, Leonardo DiCaprio’s French voice actor or as one of the most cherished comedians of the Bye-Bye, a New Year’s Eve sketch comedy special and standing tradition as one of Québec’s most-watched TV programs for the past 50 years, where he was gracing us with his impeccable and campy impersonation of our Céline Dion. Despite such fame, the interview of June 12th was framed as a difficult comeback for Legendre, after a three month-long vanishing from the public sphere. The carefully crafted image of a perfect ambassador for the modern homosexual—coupled, father of three, discreet, respectable, vegetarian—had cracked. Joël Legendre has been found guilty. Guilty of a crime deemed worthy of a front-page scandal by the journalists of the province’s number one newspaper. Guilty, after being arrested by a plainclothes officer, of cruising, another long-lasting tradition consisting of gay men gathering in undercover yet not so secret public spaces for anonymous sex encounters. Legendre’s punishment for such display of queer pleasure and sexual deviance is still effective to this day, after six years of near-complete erasure of public life.

For most queer people—and more specifically gay men in this context—shame and guilt are linked in intricate ways to more joyful feelings. The celebration of pride is a direct response to the shame pushed onto us by heteronormative society, an opportunity to respond in defiant and powerful manners. Guilt, for its part, can be linked to pleasure in a more concrete way: until 2019 in Canada, and unfortunately still to this day in some parts of the world, our sexuality has been directly attacked and criminalized in our laws, and in some ways, is still policed despite legislative changes. With this understanding, guilty pleasures not only refer to Netflix binge-watching or chocolate-eating frenzies, but also bring up a legal reality where our sexual well-being puts us at risk. Nonetheless, gay men have been cruising for what seems forever, through a multitude of adversity, through public shaming and through at least two deadly virus spreads.

Like Tim Dean reminds us, citing Gayle Rubin, in his book Unlimited Intimacy: Reflections on the Subculture of Barebacking, when the time comes to study sexual behaviours that seem deviant to some, we should not judge the apparent morality or immorality of these behaviours, as long consent between participants is respected. We should instead understand them, free of judgment, through the lens of cultural variations. My work here on cruising—and specifically as my research was conducted in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic—falls under this kind of research that Dean and Rubin write about. Therefore, I am not trying to advocate for, or justify having sex with strangers when intimacy, proximity and sexuality can lead to an epidemiologic surge. However, as a queer individual that has tested positive for both HIV and COVID-19 at some point in their life, I am aware that our ethic of care is torn between different interpretations of the situation. On one side, our history has taught us that, facing a deadly virus, we should be responsible for our health and that of vulnerable others, fostering a collective response that goes hand-in-hand with the agency of individuals. Nonetheless, that same agency is also the root of a feeling of suspicion towards a ubiquitous epidemiologic discourse reinforcing the biopower of the state and its call for community surveillance and policing. Rather than pushing abstinence injunctions disconnected from queer realities, we could prefer strategies taking in consideration the knowledge on harm reduction developed since the rise of the AIDS crisis. It is then with this ambiguous feeling that I have approached cruising in this research, as I know we all needed to make everything within our reach to stop the spread of the virus. But one cannot disregard the fact that men are having casual sex, before, during and after a pandemic, staying true to the transgressive nature of cruising; a transgression of regular sexual norms and legislation, as well as one of sanitary measures that are currently in place in most countries. It is in its capacity as a practice that follows these fine lines, bringing to light what separates the acceptable from the illegal, that cruising has always been transformative. And if one could argue that this form of spatial embodiment is rather perverse, as in deviant, I instead see cruising as a form of loitering, or flânage, linked to the prior etymological sense of perversion, which is a reversal of order, to turn things around. It is a performance of otherness and openness that “perverts” the constraints of a heteronormative spatial order, whether the world is under an epidemiologic siege or not.

I have travelled around Québec doing fieldwork for most of summer 2020, being immensely grateful for a flattened curve of COVID-19 cases that allowed me to visit cruising grounds in various regional towns without breaking lockdown restrictions. Still, the presence of active cruisers during a full-blown global pandemic was unsure, and the usefulness of my fieldwork possibly compromised. However, as I soon realized, the apparent ongoing activities proved what had been said in media and activist circles since the first lockdown: gay men learned the hard way to negotiate risky sexual behaviours and to reimagine intimacy in times of social disconnections, and they will be cruising no matter what. In this paper, I will demonstrate how the collective agency surrounding sex and harm reduction during a global pandemic can lead to a new understanding of cruising. I will also try to show how cruising—as a critical spatial practice—is turning what can be understood as shameful and deviant behaviours into a quotidian practice of queer world-making. A praxis where the guilty nature of our pleasures is a form of critique of the heteronormative society shaping our urbanities and who inhabit them. I will also try to demonstrate how it is possible, from a design perspective, to investigate cruising practices and spaces from a critical point of view, where the documentation of the fieldwork and the representation of the object of study is in a way analogous to the transgressive nature of cruising: a design methodology that aspires to the same queer world-making potentiality.

Like Queer Theory itself, sex, gender and space emerged as an area of studies in the 1990s with the publication of seminal works like Beatriz Colomina’s Sexuality & Space, Doreen Massey’s Space, Place, and Gender, and David Bell and Gill Valentine’s Mapping Desire. This latter book paved the way for the whole field of geography of sexualities and the study of spaces that are now understood as being always shaped by sexual norms enforced through, and by, lived environments. Cruising became a subject of choice to several researchers who wanted to explore the links between sexuality and public space, See Leap, William. Public Sex/Gay Space. New-York: Columbia University Press, 1999. Brown, Gavin. “Ceramics, Clothing and Other Bodies: Affective Geographies of Homoerotic Cruising Encounters.” Social & Cultural Geography 9, no. 8 (December 2008) On gendered space see Petrescu, Doina. Altering Practices: Feminist Politics and Poetics of Space. New York: Taylor and Francis, 2006. Pilkey, Brent, Rachael M. Scicluna, Ben Campkin, and Barbara Penner, eds. Sexuality and Gender at Home: Experience, Politics, Transgression. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. Rendell, Jane, Barbara Penner, and Iain Borden, eds. Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction. Architext Series. London: E & FN Spon, 2 000. Sanders, Joel, ed. Stud: Architectures of Masculinity. 1st ed. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996. On queer space see Betsky, Aaron. Queer Space. New-York: HarperCollins, 1997. Ingram, Gordon Brent, Anne-Marie Bouthillette, and Yolanda Retter, eds. Queers in Space: Communities, Public Places, Sites of Resistance. Seattle, Wash: Bay Press, 1997. On transgender architectonics see Crawford, Lucas. "Transgender Architectonics: The Shape of Change in Modernist Space". Gender, Bodies and Transformation. Burlington: Ashgate, 2015. Halberstam, Jack. “Unbuilding Gender.” Places Journal, October 3, 2018. On the architecture of sex venues see Bérubé, Allan. “The History of Gay Bathhouses.” Journal of Homosexuality 44, no. 3 – 4 (2003): 33 – 53. Ricco, John Paul. The Logic of the Lure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

If we are used to the study of queer spaces, I prefer to humbly develop a queer study of space. Rather than investigating the sociological and anthropological needs, reasons, or motives behind queer spaces, I would rather try to understand what is queer in the place-making of cruising grounds. I try to grasp on the remaining spatial qualities of this type of inhabitation of public spaces, almost as if queerness and sexuality are themselves physical materials of the built environment.

In the opening lines of the chapter “Ghost of Public Sex, Utopian longings, Queer Memories” in his book Cruising Utopia, The Then and There of Queer Futurity, José Esteban Muñoz cites Douglas Crimp’s 1989 conference “Mourning and Militancy”. As Crimp talks about a lost sexual culture to the hands of the AIDS crisis—a culture of “sexual possibilities” consisting of public sex, a variety of sex venues and rather hardcore, or non-reproductive, sex practices—Muñoz starts to develop the concept of “queer sex utopia” : "Crimp’s writing stands as a testimony to a queer lifeworld in which the transformative potential of queer sex and public manifestation of such sexuality were both a respite from the abjection of homosexuality and a reformatting of that very abjection. The spaces and acts he lists represent signs, or ideals, that have been degraded and rendered abject within heteronormativity. Crimp’s essay reclaims these terms, ideas, and remembrances and pushes them onto a list that includes such timeless values as fatherland and liberty. Crimp’s essay thus bears witness to a queer sex utopia." Muñoz, Cruising Utopia , 34

This utopia, or queer futurity, carries a transformative power that resides in its “critique of the present. ”It also “lets us imagine a space outside of heteronormativity” and“ permits us to conceptualize new worlds and realities that are not irrevocably constrained by the HIV/AIDS pandemic and institutionalized state homophobia,” Muñoz, 35 to which we could now add the COVID-19 pandemic as well. The spaces that are “carved out” from the heteronormative world by public sex cultures are not only metaphorical, but rather actual, urban spaces within the public realm. Cruising takes place in bathrooms and parks as well as in public sex venues such as gay bars and bathhouses that explicitly advertise their presence by ads, and suggestively by facades with boarded-up windows, concealing their existence from the heterosexual-by-default outside world. These spaces, their production, and their inhabitation is what interests me here. Public-sex-practices-as-critique bear place- and world-making capacities and should be of interest to a field of study like environmental design, because world-making has always been one of the primary motivations of designers.

Environmental design is not quite a discipline, but rather a transversal field of study. In his thesis on the emergence of environmental design on American campuses in the 1950s, Jonathan Lachance reminds us that the early actors behind this new field were concerned about a holistic approach to design. Lachance, “Les fondements architecturaux et écologiques de l’Environmental Design aux États-Unis, 1953-1975,” 66. Breaking down silos between traditional and professionally-driven scholarships fashioned around scales, environmental design would approach its various objects of study as a whole design science, but also from the perspective of applied and social sciences. Lachance, 66 As I myself am studying in an environmental design program, I see this transdisciplinarity as an opportunity to approach design through the lens of queer studies, where similar epistemological concerns are recurring since Teresa de Laurent is first coined the term “Queer Theory” in 1990. On Queer theory see Teresa de Lauretis, “Queer Theory. Lesbian and Gay Sexualities: An Introduction,” Differ-ences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, special issue, 3, no. 2 (1991): iii–xviii. On debates about queer studies and disciplinarity, see Jack Halberstam, “Reflections on Queer Studies and Queer Pedagogy,” Journal of Homosex-uality 45, no. 2–4 (September 23, 2003): 361–64, https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v45n02_22.In his 1998 book Female Masculinities, Jack Halberstam wrote about what he calls a “scavenger methodology”, where the queer studies researcher gathers a combination of methods borrowed from various fields and “refuses the academic compulsion towards disciplinary coherence.” Halberstam, “An Introduction to Female Masculinity,” 13. The methodology is also efficient when studying “scraps” and “gaps” left by traditional disciplines, thus its scavenger name. I believe this methodological approach can inform a transversal practice of environmental design where the “scraps” and “gaps” are found in-between traditional scales of design. The gathering of various methods across scales and disciplines makes possible the observation of existing spatial phenomena and situates the design project inside the realm of Muñoz’s “critique of the present” rather than the usual production of a new industrial good or built environment.

Marie Élizabeth Laberge talks about an “architectural culture”. Kenniff, Thomas-Bernard, and Carole Lévesque. "Inventories: Documentation as a design project." In Inventaires: La documentation comme projet de design / Inventories: Documentation as a design project, edited by Thomas-Bernard Kenniff and Carole Lévesque. Montréal: Bureau d'étude de pratiques indisciplinées; Université du Québec à Montréal, 2021.

Therefore, I would like to propose that environmental design can be understood as a queer field of studies, as it 1) sees environmental questions as transdisciplinary problems; 2) bears world-making potential through the production, investigation and critique of spaces; and 3) it scavenges scraps and gaps from peripheral disciplines to create a set of methodological tools proper to its transversal epistemology. This latter part calls for the creation of a “design culture”

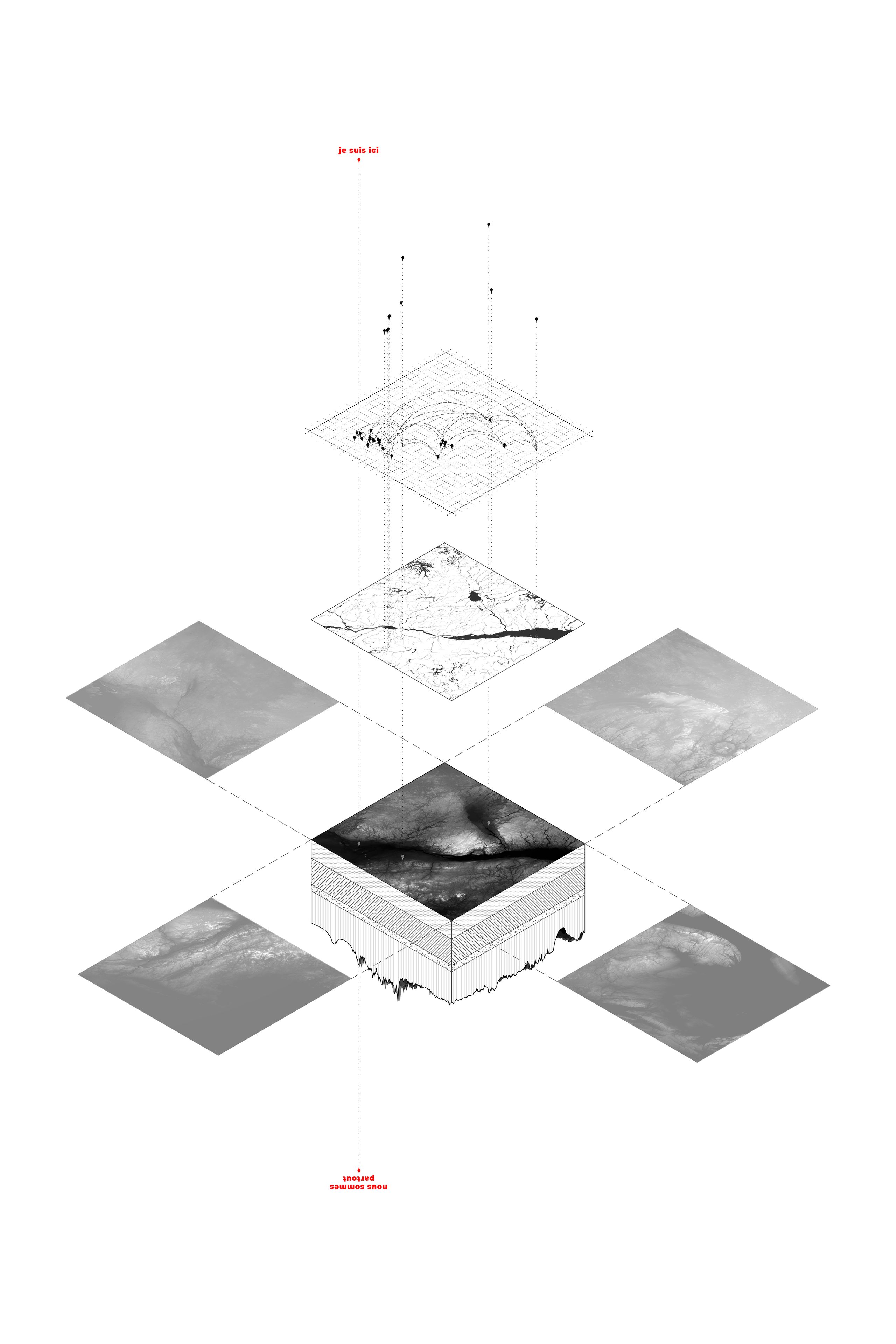

The propositional and political meaning of this method is a form of world-making embedded in design culture. Cruising is utopian, in the sense of Muñoz, by being “guilty” of the transgression of social, spatial, and sanitary norms. It is a process of space production that requires an analogous critical analysis that shares this world-making ability. Making a critical inventory of Québec’s cruising grounds appears as the adequate method of investigation for an environmental design project that has the capacity of being as queer as its object of study. Documenting and representing cruising can not only inform us of its transformative potential, but could also replicate and expand it, thus entering the realm of queer futurity through space (re)production.

It is not every cruising story that makes national news like Legendre’s. Nonetheless, cruising seems to be a recurring theme for local newspapers. I have counted and collected over 200 articles that have been written on the subject in Québec’s newspapers since 2010. I have accessed a database of French-Canadian newspapers and compiled all 206 articles covering cruising issues from January 1st, 2010 to December 31st, 2019. One significant example of this kind of media attention is the coverage of cruising at Île-Melville Park, in Shawinigan. A total of 24 articles were published over the course of 8 months. The story even made it to the local newspaper’s Year Review special issue as one of the highlights of 2010. See “Rétrospective 2010,” L’Hebdo Du Saint-Maurice, January 12th, 2011.

Halberstam, In a Queer Time and Place, 37. My translation. These are the word of Marie-Louise Tardif, former director of Île-Melville Park in Shawinigan and now Member of the National Assembly of Québec. Roberge, “Île Melville: L’Heure Est Au Grand Ménage."

I am not surprised to see cruising discourse being shaped through the lenses of moral panic, The term was first coined and developed by Stanley Cohen in Cohen, Folk Devils and Moral Panics , 9. See also Bain, Podmore, and Rosenberg, “‘Straightening’ Space and Time?” and Mason, “Of Men, Tearooms, And A Local Moral Panic.” for other examples of moral panics about men having sex outdoor in Canadian context but I am instead interested in the fact that cruising seems to be a practice discussed constantly across the province. It appears to be an issue that is not restricted to dense urban areas where there is a concentration of LGBTQ+ visibility, like Montreal and its Village. This fact disrupts the traditional and preconceived notion of metronormativity , a stereotype that often frames queer experiences as a physical and temporal journey from difficult teen years spent in the conservative countryside to a fulfilling, out, and adult life in the liberal environment of metropolises.

If in part true, this “it gets better” narrative presents bigger cities as “final destinations,” a cliché erasing the ongoing struggles and fights of the queer community in a similar fashion that gay-marriage-as-the-ultimate-goal does. It also erases a variety of queer ways of life that are not set in urban environments where a thriving LBGTQ+ community can be found. This is present in the way Québec’s regional media covers cruising stories, as the possibility of a community of gay men in need of spaces of identity representation in smaller towns seems impossible to the majority. Therefore, those caught cruising by plainclothes officers are portrayed as exhibitionist lone wolves or as “the same 12 to 15 individuals” that “are not homosexuals” but rather “sick” people.

Before, you could go downtown, there was a place. At least you knew you were free of being bothered by anyone there. There’s no place in Sherbrooke anymore, you gotta go to Montreal or Québec City. Here, in this wood, or in Victoria Park, it’s the only places. Ideally, it would be to have regulated places, you go there, you pay, you have peace of mind. Do you think a married man like me would take the risk of coming here then?"

Critical spatial practice is a concept I borrow from art critic and architecture professor Jane Rendell. Drawing from Michel de Certeau concepts of strategy and tactic, she situates them in space, underlining a distinction between some “practices (strategies) that operate to maintain and reinforce existing social and spatial orders, and those practices (tactics) that seek to critique and question them.” (See Rendell, “Critical Spatial Practice,” 2. And also Rendell, Art and Architecture: A Place Between.) Cruising is then understood as the latter, a critical spatial practice where the social order under critique within the cruising ground is heteronormativity. In opposition, current media coverage, policing and apparatuses of spatial surveillance and control are the strategies reinforcing it. Many local and global gay travel guides have been published over the years, but the case of the International Guild Guide is fascinating. Not unlike the well-known Negro Motorist Green Book, the IGG provided a list of gay and gay-friendly places, even cruising grounds, around North America and Europe through the 1960s and 1970s. In the 1968 edition, the Québec entry provides a list of spaces scattered across the province, acknowledging a queer life outside Montreal even at the time. See Guild Press, “Quebec Province,” International Guild Guide, 1968, 159–63. It is rather common to hear the assumption that “Grindr killed the gay bar.” Even Tim Dean claims in Unlimited Intimacy that sex enabled by internet “is tantamount to treating a stranger as a blow-up doll or a mail-order sex toy—an approach betokens a purely instrumental approach to the other, rather than the openness to others that cruising at its best represents.” (Dean, Unlimited Intimacy, 194.) Shariff Mowlabocus is, however, more nuanced, as he considers cybercottaging—the form of cruising, facilitated by specific websites, that takes place in public bathroom—to be a revisiting of “old haunts through new technologies” that still bears the queer qualities of classic cruising. (Mowlabocus, “Revisiting Old Haunts through New Technologies,” 433.) See also Mowlabocus, Gaydar Culture : Gay Men, Technology and Embodiment in the Digital Age. This acronym refers to “Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple” and the likes. It also refers to this overwhelming power own by a small group of tech companies located in Silicon Valley, but somehow impacting and shaping the whole world.

My fieldwork took place in 11 cruising sites of 6 regional towns with a population average of 87,730. Rather than a study of the behaviours of cruisers, I aimed to understand the phenomenon through its spatialization, trying to document and represent it with the hope of revealing a type of often overlooked critical spatial practice.

Cartography of Flows Drawing by the author Base-map retrieved from https://tangrams.github.io/heightmapper/ © OpenStreetMap contributors

As mentioned earlier, the objective of an inventory of Québec’s cruising grounds is to document and represent the practices taking place there in a way that is analogous to their critical qualities, then bearing similar queer world-making potentialities. The “representation trajectory” on my project might exemplify this quite explicitly: drawings and writings are reconstructions of the spaces I study where I try to translate the transgression I witnessed. I was interested in this analogy—where breaking the norms of architectural drawing becomes a tool to repre-sent ways in which cruising break social norms—after reading the work of Robin Evans. In his essay Transla-tions from Drawing to Building, Evans claims that architectural representation is not forever bound to the technicist culture that helped establish its scientific authority. By studying inaccuracy in a renaissance cas-tle’s plans, he states that by breaking away from architectural norms, by subverting it, these drawings were becoming “the locale of subterfuges and evasions,” (Evans, “Translations from Drawing to Building,” 186.) I have a feeling that “subterfuges and evasions” could also be what one could say about Muñoz’s queer sex utopia spaces.However, I believe the documentation trajectory, or the performance of fieldwork, should also be a form of analogy to the critical spatial practice that is cruising. If traditional techniques of field recordings are useful (photography, field notes, hand-drawn maps, and sketches), an embodiment of the cruiser’s posture in the city seemed necessary; it acts as a lens through which it is possible to see regional town urbanities outside of heteronormative understandings.

In his final chapter of Unlimited Intimacy, Tim Dean calls for an ethic of cruising, “cruising as a way of life”as he says. He argues that cruising is a state of openness to the otherness of the strangers we meet for sex, people that could be loved “yet remain strangers” in the end. Dean, Unlimited Intimacy, 180. Building on Samuel Delany’s Time Square Red, Time Square Blue, and its memory work on the disappearing public sex venues of Manhattan, Dean advocates for a form of cruising that enables contacts through different populations and demographics of closeted and out gay men. It shapes a type of social interaction that brings people together despite their differences, which cultivates a positive relation towards the Other; a type of socialization that is, in a way, ethical. Dean, 211. By saying that cruising can therefore become “a way of life,” we could argue that Dean establishes cruising as a method. He further develops on this method as being also spatial and not only interpersonal. Drawing from Allan Bérubé, John Paul Ricco, and the notion of “minor architecture” that characterize gay bathhouses, Dean portrays the cruiser as a derivative of Baudelaire’s “flâneur”. Dean, 36. The flâneur-cruiser then strolls the maze-like environments of public sex venues and cruising grounds with an “aimless aim” Dean, 36–37. echoing the openness of the sex encounters this loitering can lead to.

I am a flâneur then, a flâneur-researcher drifting on cruising grounds with the same aimlessness and openness that characterize cruising as a critical spatial practice. An unorganized, unplanned choreography that I have nonetheless rehearsed and performed many times. I narrate my experience of the sites through writings and drawings, hoping to offer a peek through the aforementioned “cruiser’s lens”. The following case studies are exercises portraying three of the sites I have visited. Three reflection and recollection of my cruising’s spatial experiences as I am quarantined in my Montreal apartment, as I am returning to my childhood town where I unpack familial traumas, and as I am visiting a region I have never been to before, but where cruising is making the headlines of local newspapers. Three sites where men are meeting despite sanitary restrictions, in real life or through my webcam. Three sites where intimacy and belonging are reconfigured through dissidence. Three sites queering the apparent banality of the urban environments they are set in. Three sites documented and represented with the hope of expanding their world-making potential.

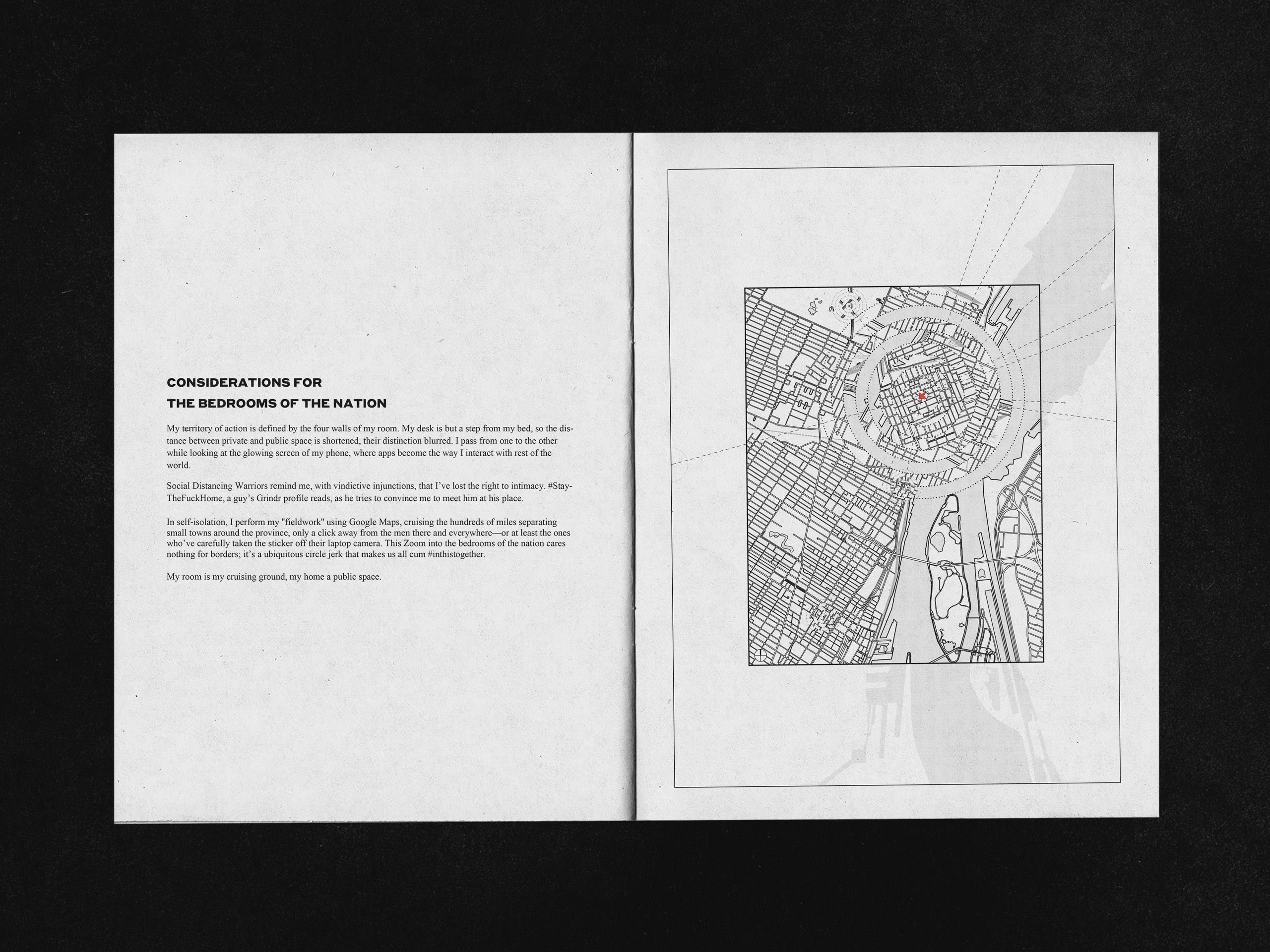

Former Canadian Prime Minister Pierre-Elliott Trudeau said in 1969, as he decriminalized anal sex between two consenting adults, that “the State has no place in the bedrooms of the nation.” Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, “There’s No Place for the State in the Bedrooms of the Nation.” The first site of my fieldwork is my bedroom, along my house and my neighbourhood; the only spaces that were physically accessible to me during the first lockdown of 2020. It is quarantined that I explored the relation between my own position in a metropolis and the remote sites I had identified as potential fieldwork locations. They appeared to me through websites and apps, offering different ways to step into spaces that are in fact only representations of spaces. These representations were at times either contradictory or complementary. A dichotomy indeed flagrant as representations provided by GAFAs —and my use of it, almost like a stalker—felt like something I could call a “surveillance gaze.” The idea of “surveillance gaze” is developed by Kurt Iveson in Public and the City, as he builds on Henning Bech’s essay Citysex: representing lust in public. Iveson, Publics and the City, 86–87. On the other hand, community-generated websites, the ones that mimic old travel guides with their listing of cruising grounds, offered me an insider’s perspective of a community I am also part of. To me, this dynamic is recreating the tension and conflict found on cruising grounds. If cruising is characterized by the tactical and critical practice of its actors, the practice itself, and spaces where it takes place, are also defined by apparatuses and strategies of surveillance that try to control or refrain dissident sexual behaviors. These two-step glimpses of inaccessible spaces, offered through (strategic) top-down GAFAs and (tactical) bottom-up web platforms, are giving a complexified comprehension of otherwise banal environments, as most cruising grounds I have identified are either left-over spaces, wastelands or open areas bordering the city. Experiencing all of this from behind the screen of my phone or computer, I also examined how cruising, in its most primary qualities that are anonymous and instantaneous sex, was being reframed by the pandemic through digital interactions such as webcam group-sex. My “fieldwork” as well as my own sexuality, now mediated by technology, transformed the reading of my immediate environment. My room became at the same time my personal space, my workspace, and the sum of all, as well as its own cruising grounds. A contradiction between social distancing and digital proximity that blurs the distinction between private and public. Something almost foreseen by Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner when they claimed, in their 1998 essay Public Sex, that “there is nothing more public than privacy.” Berlant and Warner, “Sex in Public,” 547.

Considerations For the Bedrooms of the Nation Drawing by the author

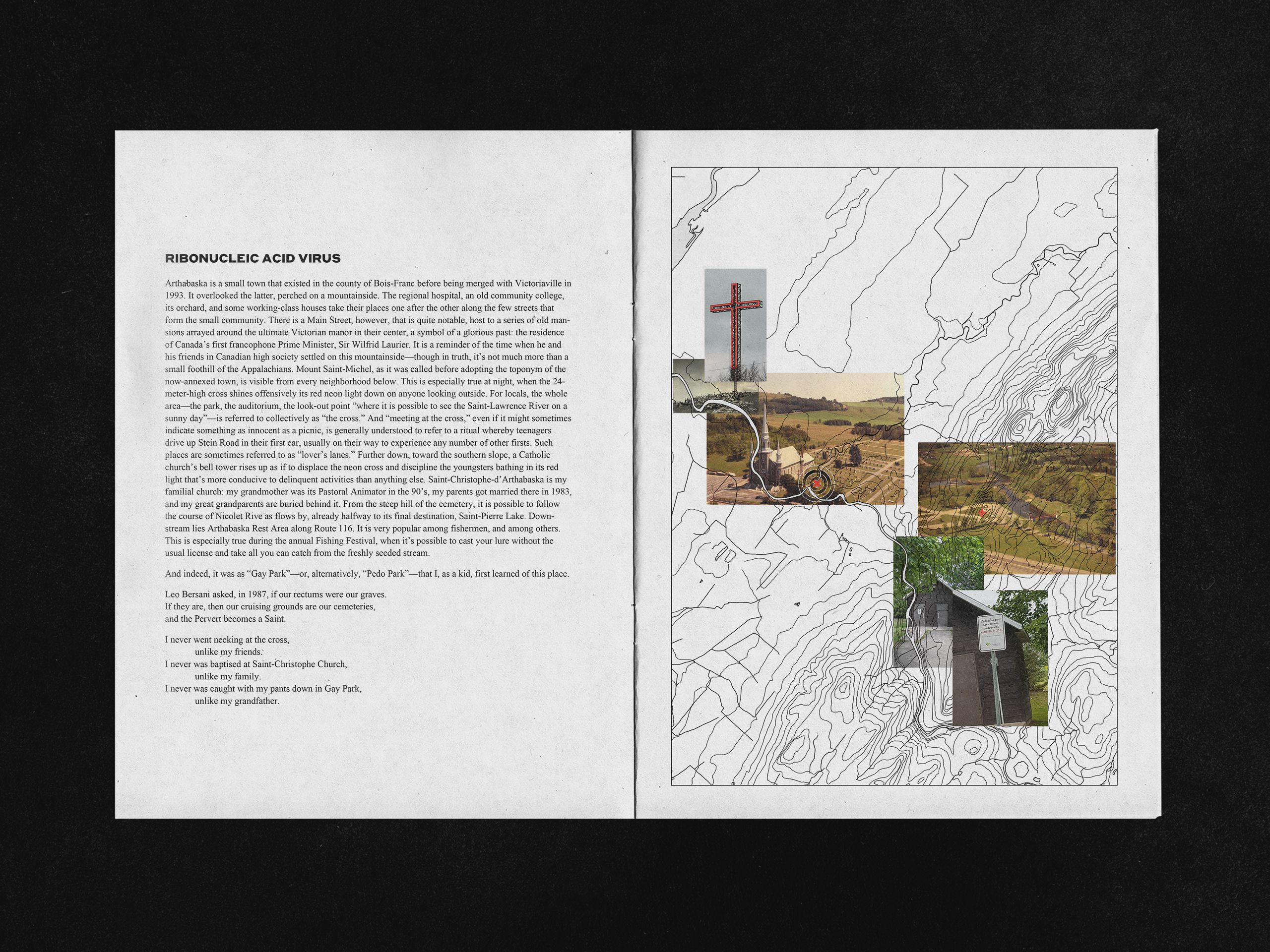

I called this case study Ribonucleic Acid Virus because this molecular configuration is another thing that SARS-CoV-2 and HIV have in common. I was interested in how cruising has been affected by previous pandemics after encountering the work of my friend and artist Jaime Ross, according to whom cruising areas should be granted landmark status for the historic role they played in the making of cities. This idea was explored in many pieces and performance from the exhibition 69 Positions: Our Vanishing curated by Ross. Ross, “69 Positions. Our Vanishing.” This bold statement reminded me of Tim Dean’s analysis of cruising in porn, specifically the work of director Paul Morris and pornstar Dawson who are famous for their representation of explicit barebacking, and implicit seroconversion. Focusing on the second film of the duo, Meat Rack (2005), Dean is describing a scene taking place in said “meat rack,” a popular cruising site in Fire Island, the popular gay seaside retreat near New York.

"As he walks away, with the camera focused on his cum-filled butt, Dawson passes another slender tree which bears the legend “SAFE SEX PINES→.” [...] By juxtaposing shots of Dawson's anal breeding with shots of traces left in the “meat rack” some years prior, this scene evokes not only the presence of men who cruised the pines and might return next summer but also the ghosts of those lost to AIDS who will never return in person. Evoking spectral presence in this way creates a sense of history, suggesting that the wooded area in which sex occurs constitutes not simply a bucolic natural setting but also an intensely historical landscape, a place where memories of previous generations linger." Dean, Unlimited Intimacy, 174.

To me, this scene and Dean’s description are the spatialization, a setting in space, of the filiation bond Dean talks about throughout Unlimited Intimacy. It is somewhat commonplace to state that queer people have reimagined kinship outside family bloodline, but according to Dean, gay men who chose to bareback, and purposefully shared the risk of HIV transmission, have recreated a set of relations based on blood and semen, forever perverting the sense of belonging. This argument is probably the central thesis of Unlimited Intimacy. “The aids epidemic has given gay men new opportunities for kinship, because sharing viruses has come to be understood as a mechanism of alliance, a way of forming consanguinity with strangers or friends. Through HIV, gay men have discovered that they can “breed” without women. Unlimited Intimacy does not take for granted what might seem obvious, namely, that bareback subculture is all about death. For some of its participants, bareback sex concerns different forms of life, reproduction, and kinship. As will become clear, barebacking isn’t merely Russian-roulette sex, that is, fucking with life and death stakes; barebacking also raises questions that complicate how we distinguish life-giving activities from those that engender death.” (Dean, 6.). It is this sense of belonging I explore through the drawing and writing of Arthabaska’s cruising ground, how these inter-personal and inter-generational relations take place in public spaces. I go back to the town that saw me grow up, where my kinship, my lineage and my heritage lie, and where my bloodline and “cumline” I borrow the term cumline— a word play on bloodline and the form of kinship through semen Dean talk about—from artist and researcher Dr. Léuli Eshrāghi, whose practice focuses on queer and indigenous kin-ships, sensual and spoken language, and ceremonial political practices. Eshrāghi, Punāʻoa o ʻupu Mai ʻo Atumotu / Glossaire Des Archipels.elders meet. I try to grasp whatever is left of a belonging feeling towards a region I flew away from, and I wonder if the queerness lingering in the town’s parks and in my own childhood memories could revived each other, revealing the formative role of cruising, even when it all feels so thin.

Ribonucleic Acid Virus Aerial pictures by Jean-Marie Cossette (1990), Point du jour aviation limitée Fund, Bibliothèque et Archives Nationales du Québec. Archival picture made accessible by Société d’histoire de Princeville. Drawing and other pictures by the author

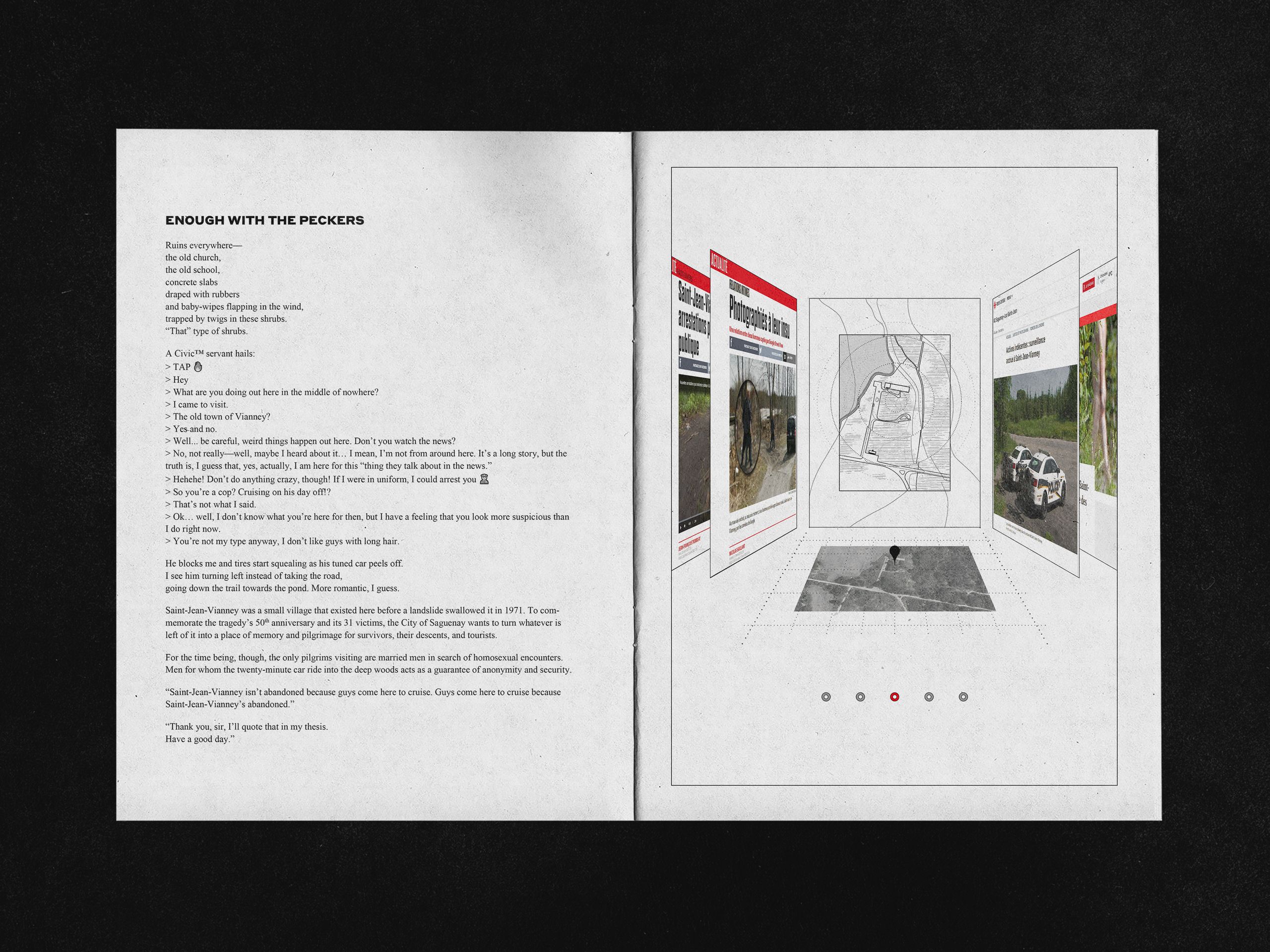

I had never visited the shores of Saint-Jean Lake and Saguenay River before summer of 2020. I had identified this region for two cruising sites that were discussed in the media around 2013 and 2014: Chicoutimi’s Hill Park and the remains of former Saint-Jean-Vianney village. I did not know however, since my survey of newspapers ended in December 2019, that I arrived exactly while a moral panic was taking over the media. “Enough With the Peckers ” is the slogan of city councillor Julie Dufour’s campaign against cruising in Vianney. Gagné, Tremblay, and Dickey, “Tolérance zéro pour les p’tits moineaux!,” 4:48. This place, that is “almost a legend֨” for its cruising, is now under massive surveillance; cameras might be installed and the local police is deploying “creative strategies” to patrol the area. Gagné, Tremblay, and Dickey, 5:00. Indeed, this heavy policing is made clear to the public as two police cruisers are stationed in front of the old church’s remains on the picture accompanying an article published on July 15th. Société Radio-Canada, “Actions indécentes.” And by police cruisers, I mean police cars, but it is also a term suiting pretty well to the plainclothes officer who hailed me on Grindr while I was doing fieldwork. I was restricted from having sex during my fieldwork by my University for ethical reasons. I was nonetheless there, strolling around in a posture I had intended to echo cruising for methodological reasons. A posture however making my intentions unclear for other men I happened to cross. When my phone vibrated and I saw the fire emoji in my notifications, I engaged with this profile showing a picture of a modified Honda Civic the same color as the one I saw parked earlier. I was not planning on having sex or trading nudes, but I was hoping perhaps for some storytelling, or information about the region’s cruising landscape. Indeed, the night before, I was warned about the ongoing situation in Vianney after a flirty guy asked me what I was doing so far away from home. I will never know the intentions of the Honda Civic guy. I will never know either if he was a real police officer or if he was only a cruiser eroticizing a type of danger that seems inherent to cruising. He might have been both, but after I hailed him back on the contradiction of his actions, to which he responded that I am “not his type,” he blocked me and disappeared from the grid of headless torsos spread across the screen of my phone. I use here the term “hailing” loosely, even if we could suggest a reading of my encounter with the plainclothes officer following the theory of interpellation of Louis Althusser. I would like to thank my friend and colleague Brian Bergstom, who helped me with the translation of my creative writing, for introducing me to this idea that will surely be explored in further projects.

This encounter had underlined quite explicitly the tension between the critical spatial practice that is cruising and the strategic surveillance the maintaining of heteronormative norms calls for. Two types of actions that are co-constructing the site itself were they take place. My position as a researcher on the field is informed by this tension on a highly guarded ground: which side am I on? Is my practice on the site still a reenactment of the performance of cruising, when instead of a hunt for casual sex I poach for traces of past cruising activities? Or is my survey of cruising grounds more of a forensic strategy , almost like the sites are crime scenes? These questions are central in my work, as I am mapping and revealing spaces that are intrinsically underground. I believe in the end that I cannot escape the “surveillance gaze” laid on cruising, whether mine or that of the society, and thus it must be included in my representation of the practice and its spaces. I also believe that, in times when everyone and every space are under the surveillance of a sanitary discourse, turning the whole country into a cruising ground and everybody into a cruiser, it is imperative to take a closer look at how communities have been dealing with such a weight of constant control, vigilance and guilt.

Times of crisis are usually times of backlash and restriction of human rights and freedom; we have all seen some of our freedoms restricted at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. In a country like Canada, this took the form of lockdowns and curfews. If we all suffered from lack of socialization, I think some queer people suffered from it in unique ways. Most of us form our kinships, our friendships and our families in manners that are unsuited to the reinforced heterosexuality put forward by the State through its sanitary restrictions. “Monogamy is preferable now”, said Québec’s Director of Public Health on the 7th of April 2020. Labranche, “«La monogamie est préférable de ce temps-ci», dit M. Arruda.” Canadians had to wait until mid-July before our health authorities suggested safer practices other than marital sex and abstinence. An official statement from the British-Columbia Center for Disease Control, probably inspired by New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene who boldly declared to “make it a little kinky” with the help of “physical barrier[s], like walls that allow sexual contact while preventing close face-to-face contact,” New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene., “Safer Sex and COVID-19.” explicitly suggested, in clearer terms, the use of “glory holes”. British-Columbia Center for Disease Control, “COVID-19 and Sex.”These statements are the product of 40 years of harm reduction knowledge. Even if a bit tongue-in-cheek, they give off an aura of queerness that would have finally made its way up to the decision-makers. But safer sex is mostly a by-product of the AIDS crisis, and, as poet and lawyer Marcus McCann reminds us, it was not developed nor implemented by health authorities in the first place: "In the early days of the AIDS crisis, gay men insisted on receiving not just the official protocols, but also the underlying public health information and pharmaceutical research. It was our communities who took that data—incomplete and contingent as it was—and used it to fashion strategies which were controversial at the time, but that we now think of as common sense." McCann, “Yes, People Still Meet for Sex in Parks. No, It’s Not a Problem.”

In the same article, McCann—who, in 2016, helped at the defense of some of the 72 gay men arrested for cruising during the “Project Marie” raids in Toronto’s Marie Curtis Park—suggests that one of the controversial yet potentially probative strategy for the reduction of COVID-19 transmission could have been inspired by cruising. He brings up this idea recalling an anonymous sexual encounter at the infamous Harlan’s Point Beach: "He does not suggest—verbally or otherwise—that I join him on the towel. He doesn’t offer oral sex or anything that involves touching. Instead, in the gentlest voice possible, with his warm eyes looking up at me, he asks me to jerk off, to cum on his face. And then lying there underneath me, he began to tug on his speedo. It was only afterwards that I realized what he was offering, from a public health point of view. No kissing or contact. No touching of any kind. His face and my face were six feet apart, consistent with the COVID guidelines for socially distant outdoor meetings, except not six feet horizontally. Six feet vertically." McCann.

Following McCann’s logic, we could say that cruising of this sort is not transgressive anymore, since it seems to follow guidelines and authorities have started to take it under consideration, but I do not believe that was McCann’s argument. Indeed, as described, cruising can be “safe” and therefore could convince more health officials to release statements like the ones mentioned above. However, cruising is not what someone would call “common sense” yet. People engaging in cruising still risk many prejudices by breaking, under constant surveillance, our social, spatial, and sanitary conventions. But it is exactly there that its transformative potential lies. To conclude, I therefore propose that cruising can be understood as a COVID-conscious tactic of safer sex that could be added to the shared and queer knowledge that generations of gay men have put forward with their sexual agency and activism. And this expands beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, as we have seen how these hard times had underline societies’ relation to intimacy, community, and control. Safer sex, risk-taking negotiation, or harm reduction, whatever we called it, are forms of critique; responses to official policies unsuited to our realities. They are part of what José Esteban Muñoz calls “critique of the present”, utopias situated here and now that offer us a peek to a possible future. These are the same queer worldmaking potentialities that reside in, and shape cruising as a spatial phenomenon; a critical spatial practice transformative of the urbanities in which it occurs.

It is hard to take pride in a practice that could harm people when hospitals are getting fuller and fuller. I can also see it is why some people chose to shame gay men for cruising during a pandemic. However, if gay shame and gay pride stand on the ends of the same binary spectrum, I suggest that guilty pleasures such as cruising might reside in the middle. They are something that goes beyond the linear comings and goings of these two opposite feelings. Something that is not “either/or” pride and shame, but rather “both/and,” thus creating a new space of queer potentialities. If cruising was not transgressive, it would not bear its utopian qualities. By standing-up and cruising despite the constant surveillance they face doing so, gay men are proving the social importance of their transgressive sexual behaviours. Being spatial practices, they underline the ubiquitous power of heteronormativity: a challenge to a strategic spatial order that enforces how people inhabit our cities. One might say that cruising is much of a perversion, and I could agree to that, even if I advocate for a broader understanding of cruising outside of sexual deviance. The etymological sense of perversion brings back to the notion of détournement, literally diversion, or hijacking and misappropriation. To me, cruisers act as agents of the diversion of public space. Flâneurs and loiterers, their presence activates queer enclaves within heteronormative surroundings, co-spatialities accessible when “you’re in the know”. Yet, when their bodies leave, queerness lingers, whether because our fluids and traces litter the ground or simply because most cruising sites share queer qualities: unclaimed, maze-like, fluid, and vague as in the French expression terrains vagues (wasteland). Or maybe because it is the only place of queer inhabitation to be found miles around. Cruising is a critical spatial practice, a quotidian practice of queer worldmaking, and if we see nothing improper in queerness, then the perversion of cruising is not a territorial misappropriation, but rather a territorial reappropriation.

An Act to amend the Criminal Code, the Youth Criminal Justice Act and other Acts and to make consequential amendments to other Acts, Pub. L. No. c 25, SC (2019).

Bain, Alison L., Julie A. Podmore, and Rae Rosenberg. “‘Straightening’ Space and Time? Peripheral Moral Panics in Print Media Representations of Canadian LGBTQ2S Suburbanites, 1985–2005.” Social & Cultural Geography 0, no. 0 (2018): 1–23.

Betsky, Aaron. Queer Space. New-York: HarperCollins, 1997.

Berlant, Lauren, and Michael Warner. “Sex in Public.” Critical Inquiry 24, no. 2 (1998): 547–66.

Bersani, Leo. Is the Rectum a Grave? And Other Essays. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Bérubé, Allan. “The History of Gay Bathhouses.” Journal of Homosexuality 44, no. 3–4 (2003): 33–53.

British-Columbia Center for Disease Control. “COVID-19 and Sex,” July 2020.

Brown, Gavin. “Ceramics, Clothing and Other Bodies: Affective Geographies of Homoerotic Cruising Encounters.” Social & Cultural Geography 9, no. 8 (December 2008): 915–32.

Califia, Pat. Public Sex: The Culture of Radical Sex. Pittsburgh: Cleis Press, 1994.

Cohen, Stanley. Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers. 3e ed. Routledge Classics. London: Routledge, 2011.

Crawford, Lucas. Transgender Architectonics: The Shape of Change in Modernist Space. Gender, Bodies and Transformation. Burlington: Ashgate, 2015.

Dangerous Bedfellows, ed. Policing Public Sex: Queer Politics and the Future of AIDS Activism. Boston: South End Press, 1996.

Dean, Tim. Unlimited Intimacy: Reflections on the Subculture of Barebacking. Chicago ; London: The University of Chicago press, 2009.

Eshrāghi, Léuli. Punāʻoa o ʻupu Mai ʻo Atumotu / Glossaire Des Archipels. 2019. Poster, 60 cm × 90 xm.

Evans, Robin. “Translations from Drawing to Building.” In Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays, 152–93. AA Documents. London: Architectural Association, 1997.

Anderson, Grant. “‘Why Can’t They Meet in Bars and Clubs like Normal People?’ : The Protective State and Bioregulating Gay Public Sex Spaces.” Social & Cultural Geography 19, no. 6 (August 2018): 699–719.

Guild Press. “Quebec Province.” International Guild Guide, 1968, 159–63.

Halberstam, Jack. “An Introduction to Female Masculinity: Masculinity without Men.” In Female Masculinity, by Jack Halberstam, 1–43. Duke University Press, 1988.

———. In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. Sexual Cultures. New York: New York University Press, 2005.

———. “Reflections on Queer Studies and Queer Pedagogy.” Journal of Homosexuality 45, no. 2–4 (2003): 361–64.

———.“Unbuilding Gender.” Places Journal, October 3, 2018.

Hooper, Tom. “Queering ’69: The Recriminalization of Homosexuality in Canada.” The Canadian Historical Review 100, no. 2 (2019): 257–73.

Iveson, Kurt. Publics and the City. Oxford: Blackwell Pub, 2007.

Ingram, Gordon Brent, Anne-Marie Bouthillette, and Yolanda Retter, eds. Queers in Space: Communities, Public Places, Sites of Resistance. Seattle, Wash: Bay Press, 1997.

Jones, Angela, ed. “Introduction: Queer Utopias, Queer Futurity, and Potentiality in Quotidian Practice.” In A Critical Inquiry into Queer Utopias. Critical Studies in Gender, Sexuality, and Culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Kenniff, Thomas-Bernard, and Carole Lévesque. “Inventories: Documentation as a Design Project.” In Inventaires: La Documentation Comme Projet de Design / Inventories: Documentation as a Design Project, edited by Thomas-Bernard Kenniff and Carole Lévesque, [pages TBD]. Montréal: Bureau d’étude de pratiques indisciplinées; Université du Québec à Montréal, 2021.

Laberge, Marie Élizabeth. “Communiquer l’architecture par le média exposition.” MediaTropes 3, no. 2 (2012): 82–108.

Lachance, Jonathan. “Les fondements architecturaux et écologiques de l’Environmental Design aux États-Unis, 1953-1975 : les cas d’Ian L. McHarg et Lawrence Halprin.” Ph.D., Université du Québec à Montéal, 2017.

Leap, William. Public Sex/Gay Space. New-York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

Mason, Fred. “Of Men, Tearooms, And A Local Moral Panic.” The Western Journal of Graduate Research 11, no. 1 (2002): 12–25.

McCann, Marcus. “Yes, People Still Meet for Sex in Parks. No, It’s Not a Problem.” Medium (blog), October 15, 2020.

Mowlabocus, Sharif. Gaydar Culture : Gay Men, Technology and Embodiment in the Digital Age. London: Routledge, 2010.

———. “Revisiting Old Haunts through New Technologies: Public (Homo)Sexual Cultures in Cyberspace.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 11, no. 4 (2008): 419–39.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New-York: NYU Press, 2009.

Munt, Sally R. Queer Attachments: The Cultural Politics of Shame. Queer Interventions. London: Routledge, 2017.

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. “Safer Sex and COVID-19,” April 2020.

“Perversion.” In The Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Petrescu, Doina. Altering Practices: Feminist Politics and Poetics of Space. New York: Taylor and Francis, 2006.

Pilkey, Brent, Rachael M. Scicluna, Ben Campkin, and Barbara Penner, eds. Sexuality and Gender at Home: Experience, Politics, Transgression. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

Rendell, Jane, Barbara Penner, and Iain Borden, eds. Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction. Architext Series. London: E & FN Spon, 2000.

Rendell, Jane. Art and Architecture: A Place Between. London: I. B. Tauris, 2006.

———. “Critical Spatial Practice.” Exhibition program. Danemark: Kunstmuseet Koge Skitsesamling, 2008.

———. Site-Writing: The Architecture of Art Criticism. Londres: Tauris, 2010.

Ricco, John Paul. The Logic of the Lure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Ross, Jamie. “69 Positions. Our Vanishing.” Exhibition. Montréal: Centre MAI, August 2019.

Sanders, Joel, ed. Stud: Architectures of Masculinity. 1st ed. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996.

Berthiaume, Claudia. “À l’amende pour un geste indécent.” Le Journal de Montréal, March 12, 2015.

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. “There’s No Place for the State in the Bedrooms of the Nation.” Digital Archive, 1967.

Gagné, Frédéric, Simon Tremblay, and Marc Dickey. “St-Jean-Vianney: ‘À Saguenay c’est maintenant tolérance zéro pour les p’tits moineaux!’” Midi Pile. Saguenay: 95.7 KYK, July 15, 2020.

Labranche, Michaël. “«La monogamie est préférable de ce temps-ci», dit M. Arruda.” Le Sac de chips, April 7, 2020.

“Rétrospective 2010.” L’Hebdo du Saint-Maurice. January 12, 2011.

Roberge, Jonathan. “Île Melville: l’heure est au grand ménage.” L’Hebdo Du Saint-Maurice. December 5, 2010.

Saillant, Nicolas. “Photographiés à leur insu.” Le Journal de Québec, February 15, 2013.

Toulouse, Ismaël. “«La forêt de la luxure» au parc Du Barrage.” La Tribune, July 25, 2014.

Hugues Lefebvre Morasse is a SSHRC Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholarships recipient, research assistant, and graduate student in Environmental Design at Université du Québec à Montréal Design School, Canada. They try to unleash the queer potential of environmental design’s project-research by studying queer spaces and urbanities, and by developing methodologies that are as queer as their object of studies. They are particularly interested in the world-making capacities of transgressive sexual behaviours and their spatialization. Their work on bathhouses, BODY HOUSES, has been auctioned at ARTSIDA X in February 2020, earning them the prize of the Emergent Artist Award.